On 7 December 2023, the government introduced legislation that would abolish the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) and establish what it terms “a new, fit-for purpose administrative review body, to be named the Administrative Review Tribunal (the ART)”. Parliamentary committees are inquiring into the relevant Bills with the safeguards against political appointees to the ART coming under scrutiny.

According to the government, the ART Act will: • Empower the President to manage the caseloads of the ART in jurisdictional lists and to assign members to jurisdictional areas in accordance with the demands of those caseloads from time to time. • Provide for a code of conduct and a professional standard for members and facilitate the professional development of members. • Empower the President to delegate ADR and case management functions to registrars to free members to focus on hearing and determining cases that are not resolved by agreement. • Provide mechanisms to enable the ART to identify, escalate and report upon systemic issues in administrative decision making, including referring them to a new Guidance and Appeals Panel or to the re-established Administrative Review Council.

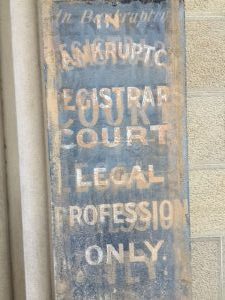

Bankruptcy law

The ART will continue to cover a wide range of areas of federal law including one particular area, being that of insolvency, both personal and corporate.

Administrative review in bankruptcy by the AAT was implemented in 1991, in effect interposing the Inspector-General in Bankruptcy (IGB) as a reviewer of trustees’ decisions, rather than the court, with a right of review to the AAT, but preserving any party’s right to apply direct to the court.

That 1991 Bill was to

“make important reforms in bankruptcy, and considerably modernise its operation by extending the application of administrative law principles to decisions of trustees and bankruptcy officials, and by introducing Administrative Appeals Tribunal review”.[2]

Objections to discharge

Requiring private registered trustees to decide issues fairly according to administrative law principles led to difficulties, for example, in providing valid reasons for lodging an objection to discharge. As the Ex Memo to the Bankruptcy Law Amendment Bill 2002 said, politely,

“trustees often have found it difficult to maintain objections. Frequently, objections have been cancelled on review by the Inspector-General (IGB), the [AAT] or the Federal Court. The reasons for cancellation vary”.

The rather unprincipled government response was not to continue to require trustees to provide valid reasons, but to remove the need for reasons to be given by trustees at all, in the case of a series of “special grounds” of objection – thereby, in the government’s words, “to strengthen the trustee’s hand [with] a tougher objection-to-discharge regime …”.

That included a rather draconian provision – s 149N(1B) – that prevents the IGB having any regard to the (compliant) conduct of the bankrupt in the period after the misconduct for which an objection to discharge was lodged. In reviewing a trustee’s decision to lodge an objection, the IGB is bound by those limiting words, and on review, so has the AAT been bound. That is, the AAT’s power is always constrained by the particular decision section involved.

Thus, the bankrupt’s argument as to the futility of the trustee’s objection in circumstances where the bankrupt said he “had nothing more to give” in compliance with his obligations, and that the trustee was simply punishing him, was rejected by the AAT in Playford and Inspector-General in Bankruptcy [2018] AATA 19.

But the Court’s power is not so limited. The Federal Court in Nguyen v Pattison [3] referred to the possibility of a court review in those very (hypothetical) circumstances where

“not only have all remedial steps been taken, but there is absolutely no utility in continuing the bankruptcy, and it is being maintained solely because the trustee is being vindictive and wishes to punish the bankrupt for past breaches of his obligations…”.

Or perhaps being simply uninformed as to the law.

In such a case, a challenge by the bankrupt to an objection to discharge would more usefully be made to the court than to the IGB or the ART, with the court able to make other orders against the trustee under IPSB s 90-15.

Review of trustee registration and discipline

In another context, in 1995, the AAT took on the oversight of the registration and regulation of trustees, in effect replacing the court process which had existed since 1928. A statutory committee would assess applicants for trusteeship with decisions of the committee being reviewable by the AAT. The

“Court will have no further role in the registration of persons as trustee, except as it would in the ordinary course of litigation where some aspect of the registration process was being disputed on legal grounds”.

A comparable statutory committee would determine matters of misconduct by trustees, again with decisions of the committee being reviewable by the AAT.[4] Hearings by the AAT are de novo.

That role will continue with the ART.

Clause 84

Subject to a review of the Bill, the existing AAT case law should still apply to the ADT. However, the Bill contains a new provision dealing with the situation where an applicant “dies or is bankrupt, wound up or in liquidation or administration”. Where an applicant is bankrupt, the section goes on to provide that another person may apply to the Tribunal to continue with the substantive application, in any case—a person representing the applicant for the substantive application; or, if the substantive application is for review of a decision—a person whose interests are affected by the decision.

The Tribunal may dismiss the substantive application if there is no person representing the applicant or the decision does not affect any person’s interests other than the applicant; or if no application to continue is made within 3 months.

In the case of a bankrupt applicant before the AAT, s 60(2) of the Bankruptcy Act provides that most proceedings of the bankrupt are a matter for the trustee to elect to continue or not. It would not be possible for the Tribunal to allow another person to continue with the application but the section may assist by allowing the trustee to become a party, either to continue the proceeding, or to discontinue.

A bankrupt can continue with AAT proceedings if they are “personal”, such as an application to review a pension entitlement. In such a case, the fact of the applicant’s bankruptcy gives no reason to change anything in relation to the proceedings.

One matter that dealt with this issue in some depth is Pitman and Commissioner of Taxation [2020] AATA 5308 where the AAT found that a bankrupt taxpayer had no standing to apply to the AAT for an extension of time to lodge an application for review of an objection decision made by a delegate of the Commissioner of Taxation. It was not clear what action her trustee took under s 60(2), merely saying that she or he “neither consents nor opposes her lodging an objection to the income tax assessments issued by the ATO”. The AAT gave useful guidance on when a bankrupt applicant would and would not be able to pursue a matter in the AAT.

Regardless, the Explanatory Memorandum merely says that

“there is no equivalent provision in the AAT Act. As a result, the AAT has a lack of clarity about progressing or dismissing such applications”.

OPC drafting

I have written about the 19th century drafting style of the status of personal insolvency by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel many times before. Home | Office of Parliamentary Counsel (opc.gov.au) In this Bill, OPC’s “modern drafting practices” produce this wording to require the termination of an ART member’s appointment, if the member

- becomes bankrupt

- applies to take the benefit of any law for the relief of bankrupt or insolvent debtors

- compounds with the member’s creditors, or

- makes an assignment of the member’s remuneration for the benefit of the member’s creditors.

The Explanatory Memorandum says that this

“guards against the potential for a member to become financially vulnerable to corruption. These circumstances are sufficiently objective and serious as to warrant termination of an appointment without discretion…”: [1303].

While (a) is clear enough, the drafting of event (b) could perhaps have been taken by OPC from the NSW Mortgages of Sheep etc Act 1845 – whereby sheep and other live-stock or their increase and progeny or their wool under mortgage were not to be subject to any law “for the relief of bankrupt or insolvent debtors” … unless the mortgage was registered 60 days prior. That one is clear.

For event (c), OPC might perhaps have relied upon various judicial definitions of compounding, from Pennell v Rhodes[5] to Haskins v Newcombe[6] as being “sufficiently objective and serious as to warrant termination of an appointment without discretion”.

As to event (d), and as we have found out before, assignments of half-pay by officers of the Royal Navy used to be void as contrary to public policy. In Flarty v Odlum[7] the Chief Justice said that “emoluments of this sort are granted for the dignity of the State, and for the decent support of those persons who are engaged in the service of it. It would therefore be highly impolitic to permit them to be assigned; for persons, who are liable to be called out in the service of their country, ought not to be taken from a state of poverty”.

But we assume that OPC and AGD know that, under current law, a Part X agreement may allow the debtor’s income, including future income, to be a source of payment to creditors [s 188A(2)(c)], and it is assumed the same would apply to a scheme or arrangement under s 73, though with no military exceptions.

It should be noted that OPC and AGD collectively deal with legislative drafting, bankruptcy and administrative review.

Progress

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs is conducting an inquiry into the Bills with a hearing on 9 February 2024. It seems the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee also has the Bills to review, to report by 24 July 2024.

Meanwhile, the AAT continues to operate, with insolvency matters of ASIC and AFSA handled in the Small Business Taxation, and Taxation and Commercial Divisions, among others.

================================

[1] Overview of draft Administrative Review Tribunal legislation | Attorney-General’s Department (ag.gov.au) The 2 bills are the Administrative Review Tribunal Bill 2023 (the ART Bill), which would establish the new Tribunal and re-establish the Administrative Review Council; and the Administrative Review Tribunal (Consequential and Transitional Provisions No.1) Bill 2023, which would abolish the AAT, make amendments to a range of Commonwealth Acts, and enable the transition of AAT staff, operations and matters to the new Tribunal. [1]

[2] Explanatory Memorandum to the Bankruptcy Amendment Bill 1991

[3] [2005] FCA 650 at [87]; see also Duckworth v Field [2023] FCA 801.

[4] See the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment Bill 1995.

[5] 9 QB 114 at 129

[6] (1807) 2 Johnson 404, Supreme Court of New York

[7] (1790) 3 D & E 681