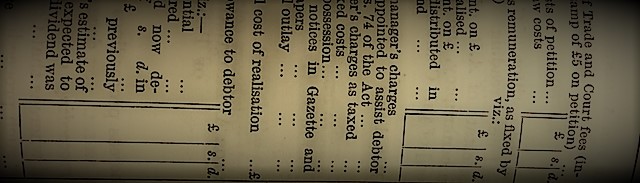

My 2022 versions of the Bankruptcy Act and the Corporations Act retain much of the process and procedure found in my 1914 edition of Williams on Bankruptcy and my 1938 Palmer’s Company Precedents.

Right now, in 2022, the numerous precedent letters, notices, checklists and timelines that we use still bear resemblance to Williams and Palmer.

All this endeavour is mostly necessary, but for all the claimed modernity of our insolvency laws, their processes are really quite antiquated.

Insolvency needs to adopt better technology.

Based on helpful communications with colleagues overseas – Finland, Scandinavia, China, New Zealand and South America – I suggest that Australia’s insolvency practice should aim for what follows.

The Insolvency Portal – TIP

All insolvencies, personal and corporate, should be held and administered electronically within The Insolvency Portal (TIP), in the nature of a government administered big data room, an area of information technology where principles, rights of access and security are already well advanced.

TIP would appear like this.

- The regulators – ASIC and AFSA – necessarily would have access to the whole of TIP.

- Insolvency practitioners would have their access to TIP divided up as relevant for the individual matters which they and their firms handle. This would include the same sort of information, reports, analyses and documents that are produced now, with professional experience and knowledge required in their creation.

- Creditors would have access to TIP in relation to their particular insolvency, in an area of TIP in which the practitioner would post reports, notices, requests and other information that any creditor needs to remain involved, at their choosing. Creditors would be notified electronically that there is information available, or sent requests – for example, to lodge their claim – to which they must respond.

- The public would have access to what is determined as a relevant set of information in TIP, comparable to the creditors or less.

Access by other bodies – the ATO, other regulators, the courts – could be assessed.

Outcomes

The beneficial outcomes of having TIP would include:

- The regulators would have ready oversight at any time;

- The insolvency practitioner would be relieved of sending reports to creditors, or lodgments to ASIC or AFSA;

- Creditors would also have access to information at any time, but with the onus on them to inform themselves, and less so on the practitioner.

TIP would offer costs saving, and efficiencies, as well as transparency and accountability.

More refined aspects of TIP could include:

- Accountability being tracked and maintained through automated auditing of who uploaded, downloaded or accessed reports, and when

- Access to reports could be ended at any given time, even after they have been downloaded from the data room

- Provision could be made for a centralised virtual ‘Q&A’ area that would allow creditors to post their “reasonable” queries in a secure, controlled environment.

Overseas experience

These ideas are not new. Finland has a web-based system administered by the Bankruptcy Ombudsman. The system receives data from the courts about all new and on-going bankruptcy or company reorganization proceedings. The system creates and builds a “debtor profile” automatically, controlled by the liquidator and the Ombudsman. Creditors can register online for their particular debtor. The system allows communication between the liquidator and the creditors, for filing claims and distributing and managing other legal notifications and documents etc. The Bankruptcy Ombudsman conducts its supervisory work by going through the debtor profiles.

Other EU countries have comparable processes, or are building them, Norway with its Brønnøysund Register Centre, www.brreg.no, and Sweden with its Bolagsverket www.bolagsverket.se. The EU itself has developed its National Insolvency Registers. England is more in line with Australia but, significantly, it has done away with most insolvency forms.

China has its Bankruptcy Platform and Columbia has online processes.

New Zealand is another example. It is much different than Australia in one respect, that the Official Assignee administers all bankruptcies; corporate insolvencies are shared with the private profession. In bankruptcy, all matters are in the online case management system – ‘OASIS4’ – launched in September 2020, which is said to make

“it faster to complete an insolvency application, file a claim or manage your account. … A new personalised dashboard means that it is easier to keep track of your applications or claims. From here you will also be able to update your personal information, apply for consent to travel or for self-employment consent with ease”.

All users need to have a secure RealMe® logon to access their dashboard and use the online services. That service applies to corporate insolvency files administered by the OA but not to the private profession.

Australia

The government’s response to the 2014 FSI Report on Australia’s financial system accepted the need for increased use of technology in financial services and regulation, supported by technology-neutral legislation to address, for example, requirements in the Corporations Act as to what must be on the “cover” or “at or near the front of” a “document”. The development of a Trusted Digital Identity Framework has been accepted, and the government’s black economy taskforce has looked at sophisticated tax tracking technology, and biometrics, and internet ‘scraping’, and use of big data, being led by the Digital Transformation Office.

In those contexts, corporations and insolvency’s reliance on Williams and Palmer might be seen by some as embarrassing.

For the moment, insolvency practitioners need to work away at their ASIC and AFSA and ARITA forms but they should also aim for the bigger picture. Means of data collection and sophisticated levels of access and security are available, in part based on sophisticated document retention, tracking and access used in data room facilities.

AFSA is making some progress, with its various on-line processes, including payments of its funding model. ASIC less so. But the financial imperatives and efficiencies are there.

Insolvency, and law and accounting, should allow their professionals to add value through their high-level expertise. While recording and reporting and information lodged through forms are important, the costs of doing so should be mechanised and minimised, to allow practitioners to attend to their more important and skilled work.

Acknowledgements: QUT’s Commercial and Property Law Research Centre, for its 2016 Personal Insolvency Conference which included many international speakers, including from the University of Helsinki; and the Bankruptcy Ombudsman Finland.

All comment is my responsibility.

[Updated and re-issued 2018; further updated and re-issued 2022].