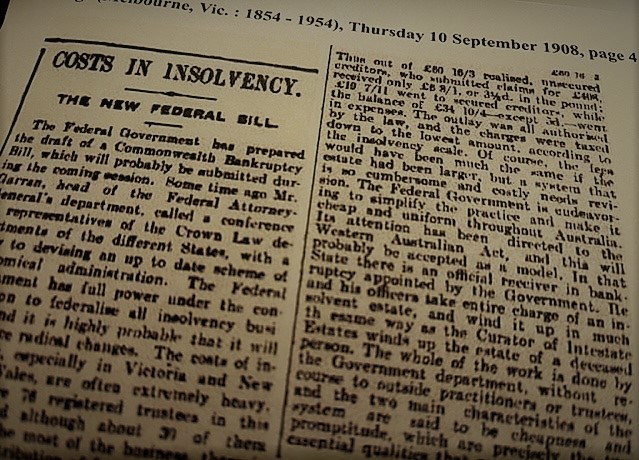

The Age newspaper in Australia has reported on what it describes as the “often extremely heavy” costs in administering insolvencies “which generally come out of the pockets of creditors who have already suffered”. It reports on some work of “extreme simplicity” charged at high rates and it refers to the many fees that “swallow up a fair proportion of the assets”. It gives an example of an estate where one third of moneys realised was paid to a secured creditor, and over a half being paid in legal, practitioner and other expenses, with unsecured creditors receiving 2% of their claims.

Before I go further, I need to explain that the Age reported this in an article well over one hundred years ago, on 10 September 1908, not long after Australia’s federation. Its context was a proposed new federal system of all insolvency law, with an official receiver, and with a focus on costs. That did not proceed, for constitutional reasons,[1] and bankruptcy law alone proceeded as proposed.

My point is that the question of costs vs outcomes in insolvency is on-going, and it may be that we just have to realise that the work done in an insolvency is or can be extensive, and that it can quickly approach or most often exceed the value of the assets remaining.

Proportionality?

While the courts readily speak of proportionality, that generally applies whether there is a large estate with a potential for a substantial recovery. Those are in the minority.

In any event, in any estate, large or small, principles need to be accepted that, for example,

“a trustee has no choice but to carry out certain statutory duties and that, in a small bankruptcy, the trustee’s costs might appear disproportionately large”;[2] and that while

“(t)he number and size of claims and the number and value of assets is an important, but not the only, element … there are many ways in which costs may be incurred which are not related, principally or even at all, to the assets and liabilities of the estate”.[3]

s put another way, “an insolvent liquidation cannot be dismissed as ‘just a case about money’”.The courts might have also mentioned that these statutory tasks are to be performed whether there are funds available or not, hence charge out rates are accordingly high, even to some “eye watering[ly]” high: Insolvency practitioner charge-out rates – the cost of carrying the State – Murrays Legal.

Even if money is available, tasks performed may not produce a moneyed result. In a case of major corporate fraud, where the liquidators spent the entire remaining moneys of NZ$330,000 without recoveries, the court was ready to accept that despite the extent of the fraud defeating them, the need for a full investigation was realised.[4]

Or, as put another way, “an insolvent liquidation cannot be dismissed as ‘just a case about money’”.[5]

Prudent people in business?!

So while the courts might say that an insolvency practitioner “must act with the same care as a prudent businessman would act in his own affairs at his own cost and risk”, a prudent businessman would hardly have regard to the public interest nor generally understand the nature of the insolvency practitioner role; nor would creditors, which is one reason why, while they can direct an IP to take a certain course of action, she or he can properly refuse.

In fact history records that so called prudent UK businessmen tried to change the nature of bankruptcy in the late 19th century in favour of creditor control, to achieve “lower costs and higher dividends”. It was a disaster, with average bankruptcy costs said to have doubled. That example of business acting in its own interests set in course the UK’s reliance on a government official receiver role that exists today.[6]

A model system?

The Age’s 1908 article in fact refers favourably to the model of a government official receiver, “without recourse to outside practitioners or trustees”, with a view to greater “cheapness and promptitude”.

That may only be saying that the costs of the insolvency system are in fact properly the responsibility of government in the first place, for which costs government may not need to fully account.

In any event, my point is that none of this is new, and while the costs/benefits of the system, which are hardly monitored in any event, are important, the whole on-going debate about them may in reality represent a threshold continuing unwillingness to recognise that insolvency work – and any professional and trade services work for that matter – costs money, often more than we realise.[7]

At an insolvency conference in 2010,[8] Mr Michael Kirby described the

“the task of insolvency administration [as being] inherently expensive. Principally this is so because of the intensive nature of the investigation of accounts (sometimes in a shambles and sometimes deliberately deceptive) that the insolvency practitioners must analyse and understand”.

And that “it is unreasonable to demand that skilled professionals should perform their functions at low cost. Dispute resolution has a cost component. Especially where the disputes are complex and contestable, as many involving insolvency are …’.

As well, the ‘returns’ from insolvency are not necessarily limited to the financial, which are so much the focus of lawyers and accountants, and regulators; its not just about the money.

===================

[1] Huddart Parker & Co Pty Ltd v Moorehead [1909] HCA 36; (1909) 8 CLR 330

[2] Simion v Brown [2007] EWHC 511 (Ch).

[3] Brook v Reed [2011] EWCA Civ 331; [2011] 3 All ER 743.

[4] Five Star Debenture Nominee Limited (in liq) v Five Star Finance Limited (in rec’p) [2015] NZHC 142

[5] In re Barlow Clowes Ltd, Millett J

[6] VM Lester, Victorian Insolvency, Chapter 5, OUP 1995.

[7] See INSOL’s remuneration Report – another perspective, 2 September 2020, Murrays Legal

[8] Bankruptcy and insolvency: change, policy and the vital role of integrity and probity, (2010) 22(2) A Insol J 4, Michael Kirby.